The RAIL Project

The Railroad and Incarcerated Laborer Memorial Project

History

When people talk about the history of the railroad in Western North Carolina, they think about how the railroad opened this backward mountain region to the outside world. However, Western North Carolina was not truly isolated prior to the coming of the railroad. By the end of the Civil War and with the coming of this reliable mode of transportation all the way from Ducktown, Tennessee, east to the low-country, the rest of the world started viewing Western North Carolina as a world-renowned resource of raw materials. The railroad provided a way to transport these materials to a global economy. Yet even today, one thing most people are unaware of when one talks about the coming of the railroad is that convict labor is responsible for the completion of what was once known as the Western North Carolina Railroad between Salisbury and Murphy.

“Hauling Railroad Crossties,” From the Forestry in Western North Carolina Collection, National Forests in Western North Carolina, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

The precedence for African American convict labor had been laid before the Civil War even began. By 1862, railroad promoters had realized that a shortage of labor was delaying the completion of the Western North Carolina Railroad. William H. Thomas, of the Cherokee Nation, and Augustus S. Merrimon from Asheville, both wrote to Governor Vance inquiring as to sending slaves from the eastern part of the state to labor on the railroad. Contracts were drawn up with slave owners and wages varied based upon unskilled versus skilled labor. However, the number of slaves available to work on the railroad was based upon that year’s agriculture, and 1860 turned out to be a banner year, which meant there was a scarcity of slave labor available to work on the railroad.

By 1864, the South was deep into the Civil War and military action had arrived on the Western North Carolina Railroad by June. General Stoneman, of Stoneman’s Raid notoriety, systematically destroyed much of the railroad on his march to Tennessee. By 1868 a bond issue was passed for new construction to extend the railroad from Morganton across the Blue Ridge and into Asheville. Native North Carolinian George W. Swepson and New Yorker Milton S. Littlefield secured control of the WNC RR. Unfortunately, Littlefield and Swepson were concerned only with their own profit and fraudulently ended up with 97% of the total stock shares in the Railroad. A commission was formed to investigate, the “Woodfin Commission” chaired by Nicholas W. Woodfin of Asheville, and when the two men received word that they were about to be held accountable for their actions, they skipped town on a train with no lights and 4 million dollars worth of looted bonds.

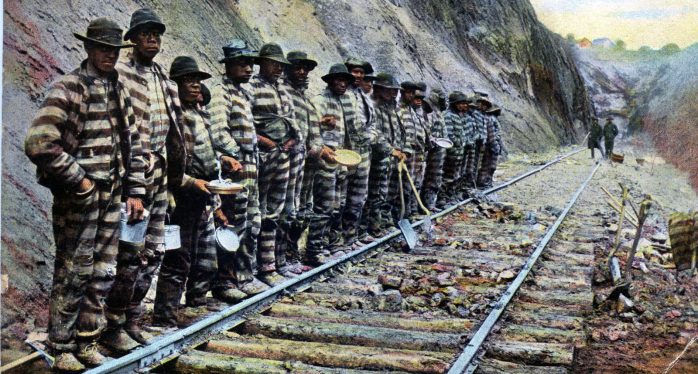

After the scandal involving Swepson and the “Prince of the Carpetbaggers” Littlefield, a new Railroad Commission was appointed and the Western North Carolina Railroad sold to Augustus Summerfield Merrimon, who was acting as the North Carolina State Agent. The new commissioners appointed James W. Wilson, a former math teacher at the state university and a Confederate veteran, as Chief Engineer. Wilson was tasked with routing the railroad from Old Fort and into Black Mountain, up and over the Blue Ridge Escarpment. During this time the Civil War had ended and the state had started using convicts for work in both the public and private sectors and it had become quite practical and lucrative. The convict labor system in the South was known as “Slavery by Another Name” as new laws made it easy to pick up any black person along the road and put them in prison. Ludicrous laws helped to bolster this, such as “pig laws,” which made the theft of any farm animal worth one dollar punishable by five years in jail, and vagrancy statutes, which made it a crime not to have a job or be able to show proof of employment. Not surprisingly, seven-eighths of the convicts in North Carolina at this time were African American.

The tiny hamlet of Old Fort was the western terminus of the Western North Carolina Railroad until 1876, and there was only one train a day each way. Passengers headed west were met by Jack Pence and his stagecoach pulled by six white horses, and they were then conveyed over the crest of the Blue Ridge into Asheville. By 1877, Wilson had been given a contract to start completing both the Swannanoa and Burgin tunnels and the majority of this work was done by convict labor. Wilson faced perplexing construction problems including poor weather conditions and heavy growth of underbrush from non-use of the tracks during the Civil War. One previously laid tunnel had even caved in during a landslide, wiping out all signs of human labor at the spot. It took almost a year to find a passable solution in the area which would be called Mud Cut.

Crossties Through Carolina: The Story of North Carolina’s Early Day Railroads, Compiled and Edited by John Gilbert, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

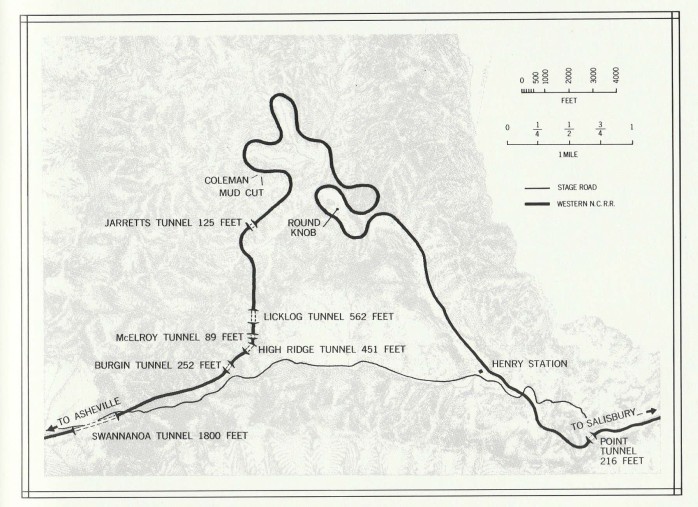

The major hardship was the actual construction of the track itself. The ascent was over 1,100 vertical feet in roughly three miles. In order to overcome this obstacle, a twisting, curving line of track was employed, which looped back on itself in order to obtain the required grade of about 2 feet per every 100 feet. This meant that around 786 vertical feet were able to be overcome in about 7.5 miles. The total curvature of the track was roughly 2,700 degrees or about 8 complete circles in order to negotiate the rise on the gradient of the mountain. It was also necessary to cut six tunnels, the Swannanoa at 1,832 feet, Lick Log at 589 feet, High Ridge at 494 feet, Burgin at 260 feet, Jarrett’s at 123 feet, and McElroy at 77 feet. To put all of this in perspective, the actual point to point distance up the escarpment is only about 3 miles.

On the W.N.C.R.R., From the E.E. Brown Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

By far, the biggest obstacle to completion was the Swannanoa Tunnel. It proved particularly daunting, and Wilson had to bore from both sides of the gap simultaneously. The small, Norris-built 4-4-0 locomotive named the Salisbury, helped with this task. It was hauled by ten oxen and a crew of almost 300 convicts hitched and driven by whips like mules over the gap. A section of track was laid and then the Salisbury advanced. Previously passed sections were then pulled up and relaid at the front end of the locomotive. On the other side of the gap, the train was slid down on a skid. The Salisbury helped haul supplies and laborers to the work sites.

“The Salisbury,” Crossties Through Carolina: The Story of North Carolina’s Early Day Railroads, Compiled and Edited by John Gilbert, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

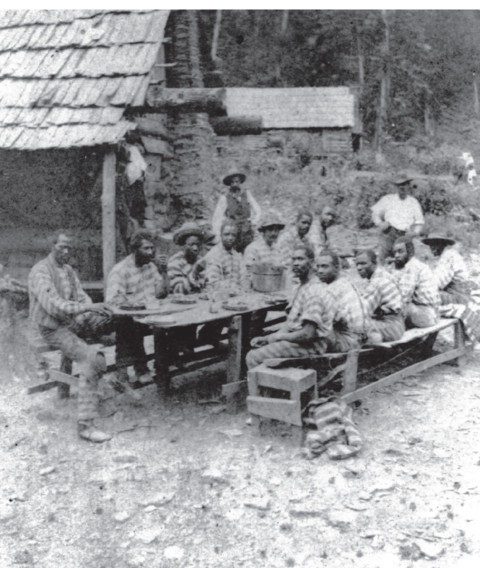

Convicts were first shipped around October 1876 to Henry Station, two miles west of Old Fort. Some reports suggest around 300 male and 16 female convicts were employed. The cash value of their work was measured at $51,000 or around 98 cents per day per worker. They built the Round Knob Stockade near Andrew’s Geyser. North Carolina had actually built a state penitentiary by 1870 and an average of 65 percent of its prison labor was taken by the construction of the Western North Carolina Railroad. Contracts stipulated that convicts would labor at least an average of ten hours each day. No person was held liable for the escape or mistreatment of any convict. Prisoners endured terrible working and living conditions, living in filthy railroad cars which were converted into jailhouses on wheels, even including iron rings to latch convicts’ chains to the sides of the cars.

Work Crew at Coleman, Crossties Through Carolina: The Story of North Carolina’s Early Day Railroads, Compiled and Edited by John Gilbert, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

By 1877, just one year later, some reports state that 430 convicts had worked an average of 7,700 days per month, and out of those convicts, 42 had escaped, 30 had died, 4 were killed, and roughly 99 were discharged or pardoned. Convicts worked sunup to sundown and were kept in various stockades between Henry Station, just to the west of Old Fort, and Swannanoa. Building the tunnels by hand proved extremely dangerous for those working these chain gangs. Since the end of the Civil War, black powder had become scarce in the South, so to solve the issue of excavating solid granite, huge pyres of pine logs were cut down by hand, stacked, and burnt to hot coals by the convicts. They would then pour cold water onto the rocks and this sudden contraction would split the rock for the tunnel construction. Nitroglycerin was also used, mixed in part with sawdust and cornmeal and then tamped into a drill hole. Convicts were not trained to handle these types of explosives, and many died, buried in countless unmarked graves right alongside the track. By late 1877, almost all convicts were being transported in from the eastern part of the state, and the climate and unvaried diet in Western North Carolina made disease a daily part of camp life. Convicts were to number at least 500 on the Western North Carolina Railroad line work and the State Penitentiary was responsible for guarding, feeding, clothing, and doctoring them. Any superior court judge could order convicts to work on the Western North Carolina Railroad. Once the line was met at Asheville, convicts were then sent to finish lines at Paint Rock or Murphy.

Photo from the Gerald Ledford Collection via Mountain Xpress

By Spring of 1879, Wilson was getting close to completion of the project and finishing the largest tunnel, the Swannanoa. Multiple cave-ins and deaths were normal occurrences. When the two crews on opposite ends of the tunnel met on May 11, 1879, Wilson wired Governor Vance the following message: “Daylight entered Buncombe County today through the Swannanoa Tunnel.” The news was hailed with delight and excitement by locals, railroad representatives, and prominent citizens alike. However, just after Wilson’s victory telegram, another cave-in occurred, crushing 20 more convicts to death. In all total, over 3000 convict laborers worked on this project and reports suggest between 125-300 convicts died during its construction. The actual cost of human life may never be truly quantifiable, but the memory of those who gave up their blood, sweat, and very lives on the completion of this monumental undertaking should always be remembered.

“Stripes but no Stars,” Fred Kahn Asheville Postcard Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library, Special Collections, UNC Asheville

RESEARCH Sources

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of Stockholders of the Western N.C. Railroad, Held in Salisbury, September 11, 1863, 1865, 1866, 1870. President’s Report, together with the Chief Engineer, and Treasurer.

Charles Lewis Price, “The Railroads of North Carolina During the Civil War,” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis from The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 1951).

Public Laws of North Carolina, 1866-1867, Ch. 98-99, (Raleigh: M.S. Littlefield, State Printer and Binder, 1867).

Thomas D. Carter. The Western North Carolina Railroad in Litigation, Washington, D.C., n.p., 1882.

David M. Holcombe, “The Western North Carolina Railroad and the State Democrats, An Era of Changing Philosophy,” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis from Wake Forest University, 1966).

Wilma Dykeman, The French Broad, New York: Rinehart and Company, 1955.

Herbert G. Monroe, “Rails Across the Blue Ridge,” in Railroad Magazine, June, 1949.

Asheville Citizen, Multiple Dates from 1878-1879.

Margaret Whistle Morris, “The Western North Carolina Railroad and the Failure of the North Carolina System,” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis from Wake Forest University, 1968).

William Hutson Abrams, Jr, “The Western North Carolina Railroad, 1855-1894,” (Unpublished Master’s Thesis from Wake Forest University, 1976).